Way back in the halcyon days of 2015 I was asked by Phil Martin and Jordan of Speculative Futures SF to make a presentation for one their early meetings. I immediately thought of one of the chapters that I had wanted to write for Make It So: Interaction Design Lessons from Sci-Fi, but had been cut for space reasons, and that is: How is evil (in sci-fi interfaces) designed? There were some sub-questions in the outline that went something like this.

- What does evil look like?

- Are there any recurring patterns we can see?

- What are those patterns?

- Why would they be the way they are?

- What would we do with this information?

I made that presentation. It went well, I must say. Then I forgot about it until Nikolas Badminton of Dark Futures invited me to participate in his first-ever San Francisco edition of that meetup in November of 2019. In hindsight, maybe I should have done a reading from one of my short stories that detail dark (or very, very dark) futures, but instead, I dusted off this 45 minute presentation and cut it down to 15 minutes. That also went well I daresay. But I figure it’s time to put these thoughts into some more formal place for a wider audience. And here we are.

Wait…Evil?

That’s a loaded term, I hear you say, because you’re smart, skeptical, loathe bandying about such dehumanizing terms lightly, and relish in nuance. And you’re right. If you were to ask this question outside of the domain of fiction, you’d run up against lots of problems. Most notably that—as Socrates said through Plato in the Meno Dialogues—by the time someone commits something that most people would call “evil,” they have gone through the mental gymnastics to convince themselves that whatever they’re doing is not evil. A handy example menu of such lies-to-self follows.

- It’s horrible but necessary.

- They deserve it.

- The sky god is on my side.

- It is not my decision.

- I am helpless to stop myself.

- The victim is subhuman.

- It’s not really that bad.

- I and my tribe are exceptional and not subject to norms of ethics.

- There is no quid pro quo.

And so, we must conclude, since nobody thinks they’re evil, and most people design for themselves, no one in the real world designs for evil.

But, the good news we are not outside the domain of fiction, we’re soaking in it! And in fiction, there are definitely characters and organizations who are meant to be—and be read by the audience as—evil, as the bad guys. The Empire. The First Order. Zorg! The Alliance! Norsefire! All evil, and all meant to be umabiguously so.

And while alien biology, costume, set, and prop design all enable creators to signal evil, this blog is about interfaces. So we’ll be looking at eeeevil interfaces.

What we find

Note that in earlier cinema and television, technology was less art directed and less branded than it is today. Even into the 1970s, art direction seemed to be trying to signal the sci-fi-ness of interfaces rather than the character of the organizations that produced them. Kubrick expertly signaled HAL’s psychopathy in 1969’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, and by the early 1980s more and more films had begun to follow suit not just with evil AI, but with interfaces created and used by evil organizations. Nowadays I’d be surprised to find an interface in sci-if that didn’t signal the character of its user or the source organization.

Note that some evil interfaces don’t adhere to the pattern. They don’t in and of themselves signal evil, even if someone is using them to commit evil acts. Physical controls, especially, are most often bound by functional and ergonomic considerations rather than style, where digital interfaces are much less so.

Many of the interfaces fall into two patterns. One is the visual appearance. The other is a recurrent shape. More about each follows.

1. High-contrast, high-saturation, bold elements

Evil has little filigree. Elements are high-contrast and bold with sharp edges. The colors are highly saturated, very often against black. The colors vary, but the palette is primarily red-on-black, green-on-black, and blue-on-black.

Mostly red-on-black

The overwhelming majority of evil technologies are blood-red on black. This pattern appears across the technologies of evil, whether screen, costume, sets, or props.

Red-on-black accounts for maybe 3/4 of the examples I gathered.

Sometimes a sickly green

Less than a quarter focus on a sickly or unnatural green.

Occasionally calculating blue

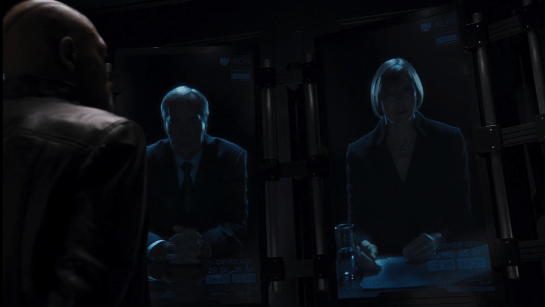

A handful of examples are a cold-and-calculating blue on black.

A note of caution: While evil is most often red-on-black, red does not, in and of itself, denote evil. It is a common color to see for urgency warnings in sci-if. See the tag for big red label examples.

2. Also, evil is pointy

Evil also has a lot of acute angles in its interfaces. Spikes, arrows, and spurs appear frequently. In a word, evil is often pointy.

Why would this be?

Where would this pattern of high-saturation, high-constrast, pointy, mostly red-on-black come from?

Now, usually, I try and run numbers, do due diligence to look for counter-evidence, scope checks, and statistical significance. But this post is going to be less research and more reason. I’m interested if anyone else wants to run or share a more academically grounded study.

I can’t imagine that these patterns in sci-fi are arbitrary. While a great number of shows may be camping on tropes that were established in shows that came before them, the tropes would not have survived if they didn’t tap some ground truth. And there are universal ground truths to work with.

My favorite example of this is the takete-maluma effect from phonosemantics, first tested by Wolfgang Köhler in 1929. Given the two images below, and the two names “maluma” and “takete”, 95–98% of people would rather assign the name “takete” to the spiky shape on the left, and “maluma” to the curvy shape on the right. This effect has been tested in 1947 and again in 2001, with slightly different names but similar results, across cultures and continents.

What this tells us is that there are human universals in the interpretation of forms.

I believe these universals come from nature. So if we turn to nature, where do we see this kind of high-contrast, high-saturation patterning? There is a place. To explain it, we have to dip a bit into evolution.

Aposematics: Signaling theory

Evolution, in the absence of heavy reproductive pressures, will experiment with forms, often as a result of sexual selection. If through this experimentation a species develops conspicuousness, and the members are tasty and defenseless, that trait will be devoured right out of the gene pool by predators. So conspicuousness in tasty and defenseless species is generally selected against. Inconspicuousness and camouflage are selected for.

But if the species is unpalatable, like a ladybug, or aggressive, like a wolverine, or with strong defenses, like a wasp, the naïve predator learns quickly that the conspicuous signal is to be avoided. The signal means Don’t Fuck with Me. After a few experiences, the predator will learn to steer clear of the signal. Even if the defense kills the attacker (and the lesson lost to the grave), other attackers may learn in their stead, or evolution will favor creatures with an instinct to avoid the signal.

In short, a conspicuous signal that survives becomes a reinforcing advertisement in its ecosystem. This is called aposematic signaling.

There are many interesting mimicry tactics you should check out (for no other reason that they can explain things like Dolores Umbridge) but for our purposes, it is enough to know that danger has a pattern in nature, and it tends toward, you guessed it, bold, high-contrast, high saturation patterns, including spikes.

Looking at the color palette in nature’s examples, though, we see many saturated colors, including lots of yellows. We don’t see yellow predominant in sci-fi evil interfaces. So why is sci-fi human evil red & black? Here I go out on a limb without even the benefit of an evolutionary theory, but I think it’s simply blood and night.

When we see blood on a human outside of menstruation and childbirth, it means some violence or sickness has happened to them. (And childbirth is pretty violent.) So, blood red is often a signal of danger.

And we are a diurnal species, optimized for daylight, and maladapted for night. Darkness is low-information, and with nocturnal predators around, high-risk. Black is another signal for danger.

And spikes? Spikes are just physics. Thorns and claws tell us this shape means pointy, puncturing danger.

So I believe the design of evil in sci-fi interfaces (and really, sci-fi shows generally) looks the way it does because of aposematics, because of these patterns that are familiar to us from our experience of the world. We should expect most of evil to embody these same patterns.

What do designers do with this?

So if I’m right, it bears asking, What we do with this? (Recall that the “tag line” for this project is “Stop watching sci-fi. Start using it.”) I think it’s a big start to simply be aware of these patterns. Once you are, you can use it, for products and services whose brand promise includes the anti-social, tough-guy message Don’t Fuck with Me.

Or, conversely, if you are hoping to create an impression of goodness, safety, and nurturance, avoid these patterns. Choose different palettes, roundness, and softness.

What should people not do with this?

As a last note, it’s important not to overgeneralize this. While a lot of evil, like, say, Nazis, utilize aposematic signals directly, some will adopt mimicry patterns to appear safe, welcoming, and friendly. Some evil will wear beige slacks and carry tiki torches. Others will surround themselves with in-group signals, like wrapping themselves in the flag, to make you think they’re a-OK. Still others will hang fuzzy-wuzzy kitty-witty pictures all over their office.

Do not be fooled. Evil is as evil does, and signaling in sci-fi is a narrative convenience. Treat the surface of things as a signal to consider, subordinate to a person—or a group’s—actual behavior.